Staking Income for Validators: How to Recognize and Report Rewards under US GAAP

Validator staking rewards are often misunderstood in financial reporting, and many companies struggle with how the income should be measured, recognized, and presented.

Background

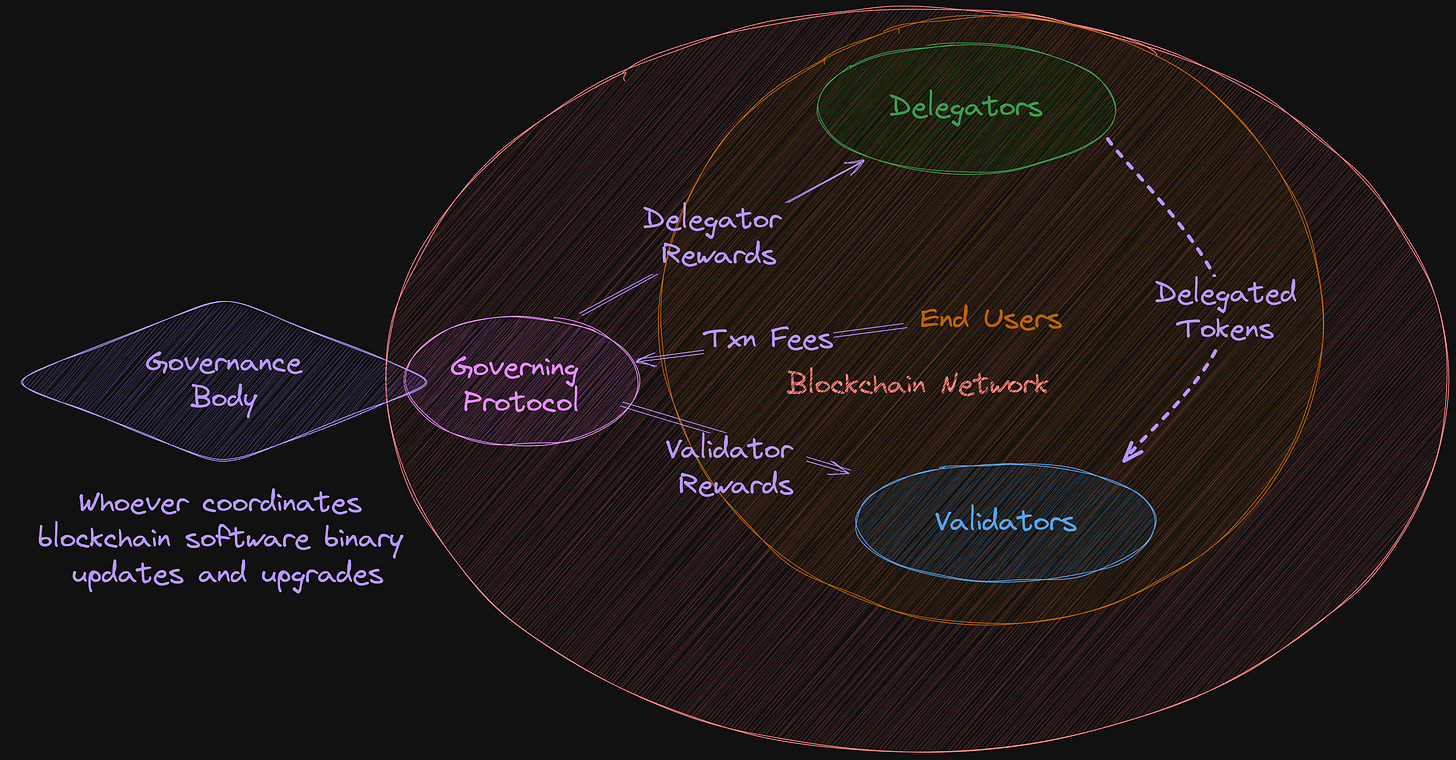

On proof-of-stake blockchains, the network's security is ensured by users who stake their scarce resources (crypto assets) on chosen validators. This is how it happens.

Validators deploy blockchain software binaries (compiled protocol code) on servers, whether owned or rented, that function as nodes on the blockchain network. This software enables validators to verify transaction accuracy and sequence and group validated transactions into blocks.

Validators are chosen from a pool to propose new transaction blocks. The selection follows protocol-specific rules that typically consider factors such as the number of staked tokens and a node's historical performance (e.g., past instances of downtime and double-signing). But to be added to the blockchain, each new block must achieve consensus among a set percentage or number of active validators. To achieve consensus, validators vote on proposed blocks using digital signatures generated from each node's private key. A validator's power to vote on proposed blocks directly corresponds with the number of tokens staked with the validator. Once voting is complete and a consensus has been reached, the newly forged block is added to the blockchain. The need for consensus means that any attacker on the PoS network must control a majority of the native tokens to succeed in a 51% attack. Thus, staking is designed to ensure the security of the blockchain network.

Validators earn rewards in two primary ways:

First, by staking their own tokens, they receive staking rewards proportional to their investment.

Second, they share rewards with other users (delegators) who decide to stake their tokens with them by delegating them to validators.

Thus, the reward system benefits both validators and delegators, providing two streams of income: direct staking rewards for validators and shared rewards for both parties.

In addition, validators often enter into agreements with blockchain foundations (or similar entities responsible for network governance), in which the foundations allocate returnable grants from the massive balance of native tokens to validators and give up delegator rewards for the benefit of validators. Foundations do this to incentivize validators who enter the ecosystem early. The rewards earned by validators on these assets are roughly 5-8%, compared to 0.01-0.05% for assets staked by delegators not affiliated with the Foundations (although these reward rates can vary widely across networks and over time due to changes in network policies, token economics, and market conditions).

Each blockchain is unique, and there are different variations of PoS. Some networks allow anyone to join as a validator as long as the new entrant has sufficient stake (e.g., 32 ETH on Ethereum), others have a limited number of validators (e.g, only 105 validators can be active on the Polygon network), and others have a combination of both (e.g, in the NEAR ecosystem).

With this in mind, let’s dive into a few questions specific to staking revenue accounting in the financial statements of proof-of-stake validators in light of the requirements of ASC 606 “Revenue from contracts with customers”:

Know Your Customers. Who is the reporting entity’s customer?

Principal vs. Agent. Is the validator a principal or an agent in staking revenue arrangements?

Consideration Payable to Customers. Do delegator rewards fall under consideration payable to customer guidance?

Accounting Treatment of Validator Staking Income under US GAAP

Know Your Customers

The structure of staking arrangements is complex because it involves multiple parties acting as customers from the perspective of a validator. These customers are also directly involved in the provision of services by validators.

We can identify the following key parties of staking arrangements:

Blockchain networks. Network protocols may be controlled by another business or nonprofit, or governed in a decentralized manner. As such, it is appropriate to identify the network as a separate entity. This entity may act as a customer of the validator. The network’s role is to pool transactions and allocate them to validators, who are responsible for building new blocks of the blockchain from those transactions in compliance with the established protocol rules.

Users. The role of network users is to execute transactions on the blockchain. There are two subtypes of users:

End users who want to send crypto to another party or buy an NFT on a blockchain initiate transactions by submitting them to a blockchain client (e.g., a wallet). The client broadcasts submitted transactions to the network for validation. Validated transactions are included in a new block appended to the blockchain. Once a block is appended, the transaction is included in the blockchain. End users are the ultimate consumers of services provided by validators. However, end users should not be viewed as direct customers. They should be viewed as direct customers of the blockchain. Blockchain acts as an intermediary, setting protocols for network operation and for interactions between users and validators.

Delegators. Delegators are a subgroup of end users who engage validators to provision validation services to all network users. Delegators stake their limited resources to secure the network through the protocol’s built-in mechanism. Many (but not all) protocols transfer voting rights embedded in the staked assets from delegators to validators. To choose validators or to purchase crypto assets for staking, delegators must execute transactions on the blockchain network (either directly via an on-chain interaction with a staking smart contract or via the mechanism established by the custodian of the crypto assets). This means that delegators are customers of the protocol entity. However, staking arrangements do not oblige validators, nor do they oblige delegators, to pay any consideration in exchange for validation services rendered.

Staking arrangements include contracts between validators & delegators as well as validators & end users. Under ASC 606, both of these contracts should be combined and analyzed as a single arrangement because:

Delegators are always participants in the network.

Consideration payable under arrangements with delegators depends on the performance and rewards earned by validators in the arrangements with end users of the network.

As such, contracts with delegators are only contracts with customers to the extent that they are combined with validators’ arrangements to validate transactions on the network. Therefore, we can identify that:

Delegators are de jure customers.

Blockchain networks are de facto customers who engage validators to perform validation services.

End users are indirect customers who consume the results of services delivered by means of the blockchain protocols.

Contract Combination Analysis

Institutional delegators often enter into separate formal legal agreements with engaged validators. These agreements might or might not modify the protocol's standard rules regarding validator commission levels, guarantees against potential slashing losses, or eligibility conditions for performance bonuses.

FASB ASC 606-10-25-9 will likely require a reporting validator entity to combine those contracts and account for them as a single contract because all three conditions for contract combination have been met:

Both contracts have a single commercial objective.

The second contract modifies the amount of consideration receivable under the standard blockchain protocol terms.

Services provided under both contracts constitute a single performance obligation to validate network transactions in accordance with the blockchain protocol rules.

Principal vs. Agent Analysis

ASC 606 requires us to assess whether we act as agents or principals for each good and service transferred to customers when other parties are involved. Staking services represent a single performance obligation. These services are performed for the blockchain networks AND delegators, as both customers are contracting with validators for the same service (transaction validation on the network), which represents a single combined performance obligation to ensure that the validator nodes are running with maximum up-time in a manner reasonably intended to arrange for the generation of digital asset rewards for delegators. Since there is only one service and validators are primarily responsible for such service, they are (clearly) the principal1.

In the US, public companies with significant staking revenues earned as validators are generally treated as principals in staking arrangements (with exceptions, such as SharpLink Games, Inc.; see the accounting policies section here). This is because, as validators, they control the only service being provided (transaction validation on blockchain networks). As such, we can find in these companies’ SEC filings disclosures stating that management records the gross amount of both validator and delegator rewards from staking as revenue. This is consistent with our conclusion above.

Analysis of the Guidance on Consideration Payable to Customers

The guidance on consideration payable to customers requires companies to assess any payments made to customers to determine whether they were made in exchange for a distinct product or service. Based on this understanding:

Payments made without distinct services or goods received in exchange are treated as a reduction in revenue.

Payments equal to or less than the fair value of distinct services or goods received are accounted as costs of goods or services purchased2;

"An entity needs to determine whether consideration payable to a customer represents a reduction of the transaction price, a payment for a distinct good or service, or a combination of the two".

Depending on the blockchain, delegators act as either direct or indirect customers of validators. Because delegators are customers, rewards paid to delegators are subject to the guidance on consideration payable to customers. It would be easier to understand this issue if we accounted for the fact that the validator may never obtain control over delegator rewards, as these rewards (with rare exceptions) are automatically distributed to delegators by the protocol. However, both the delegator’s and the validator’s rewards are transferred in exchange for a single performance obligation (the validation of transactions on the network). The form/method of settlement does not affect whether the payment should be included or excluded from the transaction price (refer to Questions 25-26 of the Revenue Recognition Implementation Q&As published by FASB for further discussions).

The consideration payable to customers’ guidance applies to payments made to any customers in the distribution channel, including payments made in cash, equity instruments, or items that can be applied against amounts owed to the entity [606-10-32-25]. As the native cryptocurrency of the network can be applied against amounts owed to validators for services on this network, token payments to customers are subject to the guidance on consideration payable to customers. This, in particular, means that the transfer should be measured at the fair value of the tokens at the contract inception date rather than at the cost of the digital assets transferred to customers.

As such, our analysis may follow one of the two routes depending on whether a validator is believed to receive a distinct service(s) in exchange for delegator rewards:

If delegation is not viewed as a distinct service, then the guidance would require us to reduce the transaction price by the amount of consideration payable to customers. This is because delegator rewards are paid in tokens, and delegators can apply these tokens against amounts owed to validators for transactions executed on respective blockchain networks. Hence, the noncash form of payment does not preclude us from accounting for these payments under the guidance for consideration payable to customers. As no distinct services are provided in exchange for consideration transferred to customers (delegators), these rewards should reduce the revenue reported in the validator's financial statements.

If we were to conclude that delegation is a separate service (distinct from validation), it would imply that the primary responsibility for delegation services lies with delegators rather than validators. Hence, validators would act as agents of delegators, and related rewards would be presented by validators on a net basis.

Since the validator is a principal, rewards paid to delegators (customers) fall under the scope of the guidance on consideration payable to customers. Because no distinct service is being received in exchange for rewards transferred to customers, delegator rewards must be deducted from the transaction price. So, even though the validator is a principal, validators should present revenue net of delegator rewards.

Consensys recently brought up a different point of view that ultimately also supports the net presentation. See their communication with the SEC here.

To Be Continued…

Today, we discussed the accounting for staking revenue from the perspective of validators. We focused on the accounting treatment of staking income from the perspective of validators. For a comparison of how validators and delegators differ from an accounting perspective, see my companion article on delegator staking income

KPMG was the first Big Four company to address staking accounting explicitly. Based on KPMG’s Accounting for crypto staking rewards, in a typical staking arrangement, a validator acts as a principal because it controls the service. Hence, it should account for staking rewards on a gross basis.

The costs of purchases are not the same as the costs of sales. The cost of sales is a line item on the income statement (an expense). Costs of purchases include both costs capitalized as part of assets on the balance sheet and those expensed as part of any expense category in the income statements.